Do contemporary artists have predecessors? Are there any other traditions besides Oscar Hansen’s Open Form? In his Masters (2004), a series of bogus articles published in the mainstream press, Zbigniew Libera references a few of his favorite yet underrated artists: Zofia Kulik, Anastazy Wiśniewski, Jan Świdziński, and Andrzej Partum. “Partum is Dead” announced the headline of the daily Gazeta Wyborcza, edited for the occasion by Libera himself.

Piotr Uklański, Untitled, 2011

Piotr Uklański, Untitled, 2011

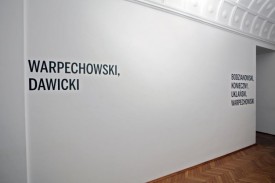

photo: Piotr TomczykIn his 2009 book on 1970s Polish avant-garde art, Łukasz Ronduda addressed a series of attitudes that preceded contemporary artistic strategies. Piotr Uklański took over the visual side of the book, interpreting 70s art in his own way and transforming a scholarly publication into a shiny, colorful album. Ronduda has just opened an exhibit at the Museum of Art in Łódź, showing the direct links between middle-aged artists such as Cezary Bodzianowski, Piotr Uklański, Oskar Dawicki, and those one generation their seniors — Zbigniew Warpechowski and Marek Konieczny, both of whom represent post-essentialism, one of the movements selected by the critic.

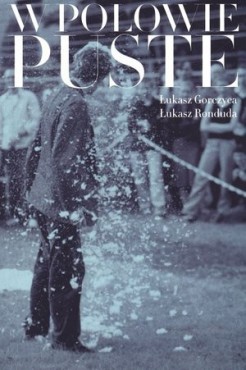

Concurrently, Ronduda wrote a novel titled Half Empty (W połowie puste) along with Łukasz Gorczyca, a former editor of the legendary “Raster” and current co-owner of an esteemed private gallery under the same name. The main character of the book is Oskar Dawicki, a popular artist, performer, and socialite. An entire constellation of characters appear under the guise of pseudonyms (Generał, Najdroższy, Lansas, Lady Orez), as do the authors themselves. The names of trendy Warsaw clubs are dropped, and as in any true art world, rainbow brigades make their mandatory appearance. Dawicki is elevated to the status of a Warsaw legend. It’s no wonder that Poland’s entire contemporary art world has been captivated by Half Empty for the past few weeks, trying to sort out truth from fiction. In our tiny backwater, the novel has stirred up as great a commotion as The Da Vinci Code.

You are laughing at yourselves

Łukasz Gorczyca, Łukasz Ronduda

Łukasz Gorczyca, Łukasz Ronduda

Half Empty, Lampa, Warsaw, 333 pages,

in bookshops from February 2011Half Empty is a reversed biography of Dawicki. Each chapter takes us back in time, and the blank first half of the book remains a puzzle about the future: “Oskar didn’t believe in the future, he just knew that it didn’t have anything to offer someone like him.” We never find out if his mother’s prophecy, “You’re going to die like a slave”, comes true. Then there are less obvious characters such as the mysterious curator Sośnicka, who represents all the worst qualities commonly associated with art curators and the numerous offenses committed by curators in recent years, including the creation of pieces in the artist’s name and without their consent (e.g. Schism at Warsaw’s Centre for Contemporary Art).

The book ends with a description of Dawicki’s ancestors written by his grandfather, somewhat reminiscent of the genealogy of Jesus Christ as presented in the Gospel. The account of the Dawicki family history is presented in the Kociewie dialect. The artist comes from Starogard Gdański. He imagines himself eating a pork chop that is Poland, cutting out each individual region but leaving Kociewie intact. The book’s strongest points are its shifts in scale, space (such as the use of a urinal as a source of rain over New York City), and time (a pub crawl is presented as guerrilla warfare during the Warsaw Uprising). I couldn’t put it down myself.

But the concentration of jokes per square inch of paper makes you feel as if you’ve accidentally sat down with a bunch of tipsy strangers speaking in an incomprehensible code. Fortunately for the reader, footnotes come to the rescue. Some of the code words are a bit raunchy, and is anyone still amused by scatological jokes about exhibitions devoted to poop? But after all, just as in Dawicki’s art itself, conscious embarrassment is part of the point. But if “Raster” (Gorczyca and Michał Kaczyński) used irony a decade ago in their struggle against the “system” (inherited from yet another system), then what battle are these jokes intended to wage today? I’ll answer that question at the end.

Sweet, Fabulous, Divine, Heavenly

Ronduda’s show in Łódź actually consists of two separate exhibitions: the first depicts the master/apprentice relationship between Warpechowski and Dawicki, while the other explains the ties between Konieczny and Warpechowski, and Bodzianowski and Uklański. Warpechowski was a personal acquaintance of each of them, while Konieczny ran a peculiar workshop at Warsaw’s Academy of Fine Arts for a year. The latter, as is becoming of any radical anti-institutionalist, pulled out of the exhibition at the last minute. He’s still there, in a way, as everyone mentions this fact, but he is at once absent, as not one of his pieces are on display. It seems we won’t find out whether his silence is overrated.

photo: Piotr TomczykThe exhibition primarily does justice to the somewhat forgotten Warpechowski. Dawicki visited the old artist at home in Sandomierz, where the master and his students held private performances. The young artist claimed that one of Warpechowski’s performance pieces played a formative role in his own art. He described the performance in an interview: “With enormous effort, Warpechowski hoists an enormous rock and then throws it as far as he can, repeating the process many times until the rock is replaced by a tiny feather. Both the rock and feather are equally resistant and travel an equally short distance.” As it turned out, the performance never actually took place, and was nothing more than a projection on the part of Dawicki. The artist and curator managed however to convince Warpechowski to go through with the made-up performance.

photo: Piotr TomczykThe exhibition primarily does justice to the somewhat forgotten Warpechowski. Dawicki visited the old artist at home in Sandomierz, where the master and his students held private performances. The young artist claimed that one of Warpechowski’s performance pieces played a formative role in his own art. He described the performance in an interview: “With enormous effort, Warpechowski hoists an enormous rock and then throws it as far as he can, repeating the process many times until the rock is replaced by a tiny feather. Both the rock and feather are equally resistant and travel an equally short distance.” As it turned out, the performance never actually took place, and was nothing more than a projection on the part of Dawicki. The artist and curator managed however to convince Warpechowski to go through with the made-up performance.

Ronduda decided that the situation was symptomatic. If the Polish avant-garde artists of the 70s have been forgotten, then ideologically similar artists who could have been inspired by the experiences of the older generation had to instead create their own masters. Referencing Mieke Bal, he writes about “reverse pioneers” and preposterous stories — ones that mix the “pre” with the “post”.

Dawicki and Warpechowski enter into a dialog. Ronduda places special emphasis on the existential and vanitas themes in the work of both artists. Konieczny’s withdrawal, which allowed him to avoid the preposterous logic of the exhibition, cast a shadow over the more subtle themes sketched by the curator. The simple, energetic performances by Warpechowski (e.g. “Rąsia”, 1981) correspond with the work of Bodzianowski, while the enormous word “Azja” (1989), styled after the decorative propaganda of the previous system, dovetails with the interests of Uklański, who tests the semantic volume of symbols. Uklański also links all the featured artists together with an impressive graffito that read: “Sweet Warpechowski / Fabulous Konieczny / Divine Bodzianowski / Heavenly Uklański”.

After conceptual art

While there is a typical historical and artistic logic to the exhibition, the new book by Gorczyca and Ronduda is an exceptional idea for a new language with which to write about art — literary fiction. It allows us to see art from the perspective of the artist, not the obligatory discourse. “I was screwed by discourse,” Dawicki liked to say. Never again will I see Dawicki’s performance pieces in a neutral light. If Dawicki doesn’t show up at his own performances (for which he incessantly apologizes), it means he’s probably indulging in his favorite pastime — getting lost. “There’s nowhere to get lost. Shit, I think I know where I am,” he said, irritated during one trip to Sandomierz.

Dawicki’s art is more about what he doesn’t do, rather than what he does. He doesn’t make art about the Holocaust, he shows up late to his own performances, and he makes his getaways by jumping out of windows. And when he actually does something, he employs gags, jokes, and slapstick humor. The tireless Dorota Jarecka recently described him as “Poland’s greatest parodist and metaphysicist.”

Zbigniew Warpechowski, Asia, 1989-2011

Zbigniew Warpechowski, Asia, 1989-2011

photo: Piotr TomczykProving that Dawicki isn’t an escapist demands significant linguistic gymnastics. Ronduda thus writes about his “masochistic emphasis of the void” and the void “that is the basis of all contemporary artistic gestures”. According to the critic, Dawicki poses “ontological questions on the essence of art and existence”, while merely confirming “the crisis of the language used to ask similar questions”. He is left to “work with the void”. There’s more void here than in Kierkegaard. When Warpechowski leaps towards the sky from a knoll (“Prayer for Nothing”, 1974), Dawicki responds with a photograph displaying him leaping to the bottom of a ravine (“Little Ado about Nothing”, 2010).

The problem addressed by Ronduda is nevertheless much broader. He is curious to see what is filling the void left by conceptual art, how today’s artists ask the fundamental questions “What is art?” and “What is a being?” — questions they’re obviously asking, while avoiding the answers. And finally, “How are are we supposed to make art that isn’t about something?”

Escaping discourse on a shiny chopper

In Half Empty, that despised discourse which destroys “true art” with its power is equated with the “groundbreaking” exhibition on poop curated by Sośnicka and one critic’s request for a higher chair. While Dawicki might boast about the number of exhibitions he has failed to attend, he would be no one without the critics and curators. And while Konieczny eschews public institutions, Dawicki is the best example of a kind of institutional criticism that perceives art from the perspective of artists and with their help. When Dawicki frames a piece of paper with the words “I’ve never done a piece about the Holocaust” and hangs it up in a museum, he is at once doing and not doing said piece. And what would be left of his character if all the footnotes were removed from Half Empty?

It is precisely this tension that Half Empty and Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction have in common. The latter is an ambiguously-titled, uncanny crime film in which plot twists all revolve around the most embarrassing of human orifices. Vince gets into trouble and ends up dead after spending too much time in the toilet, while the whole intrigue is spun around a watch that Butch’s father kept hidden up his poop chute as a POW in Vietnam. Perhaps “getting screwed by discourse” isn’t what the artists fear, it’s “getting screwed” — bottom shame. It’s as if these male man-artist who associate with male groups of men (Hlasko, Komeda, Polański) want to submit to it, but are afraid of getting dirty.

In the final scene of Pulp Fiction, Bruce Willis — the unviolated one who avenges his father’s death — rides off into the horizon on a beautiful chopper. Half Empty doesn’t have an ending, but it expresses a similar hope for virginity left intact. That, as it turns out, is why the artist needs the curator.

Bodzianowski / Konieczny / Uklański / Warpechowski and Warpechowski / Dawicki. Museum of Art in Łódź. Curated by: Łukasz Ronduda. 22 February – 3 May 2011.

translated by Arthur Barys