Ziemilski makes novel use of the theatre’s potential as a place in which to stage intimate events, games and experiments; the word “performance” isn’t quite accurate in the context of this director’s work. The potential is apparent: we welcome unforeseen transgression in the theatre, because we normally observe it from the comfortable passive perspective of the audience.

The creator of Prolog (Prologue) takes advantage of the rich potential afforded by the space of the theatre, but only to place the audience within it safely. You might even get the impression that Ziemilski has gone to great efforts to spare his viewers any unnecessary physical contact with typical theatrical artifacts: there’s no sitting around in the seats, no creaking, no darkness and no programme. He needs the space of the theatre as much as a plane needs a runway; the whole event takes place in the heads of individual audience members. The intimate atmosphere — devoid of sentimentalism, drama and irony — evokes a sense of security. Keeping an open mind, you let the feeling of blissful relaxation and irrational carelessness wash over you, while the voice in your headphones strikes you as trustworthy, much like the voice inside your head, and you willingly submit to its instructions.

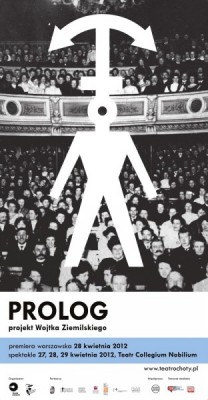

Prolog, concept and direction

Prolog, concept and direction

by Wojtek Ziemilski, Warsaw

premiere in Teatr Ochoty,

28 April 2012Ziemilski has already exploited intimacy as a catalyst for reflection unhindered by fear and conventions. In Mała narracja (Small Narrative), which the director describes as a performative lecture, he made the audience auditors of his own internal thought process, one provoked by accusations of his grandfather’s alleged collaboration with the communist secret police. Stripped of any gimmickry or attempts at emotional blackmail, the erudite monologue offered the viewers the sense that they were participating in something extraordinarily personal, as if the audience were planted into the mind of the author (hence that sensation of being removed from the space of the theatre).

In Prolog, the director takes a step in the opposite direction: the game is played in the mind of the viewer. To participate, you must first let a voice/guide into your head. This voice gives you instructions to follow and, more importantly, it narrates the events, posing questions to provoke reflections that balance between issues of community (Who are these other people? How are they reacting to this situation? To what extent are we in this together?) and an internal conversation moderated by the voice (To what degree am I consciously controlling my outward reactions? How much about me does this situation reveal? And what exactly does theatre mean to me?).

The voice/guide directs each viewer’s attention to the others (audiences number fifteen people). Following his instructions, you observe each other throughout the stages of the pieces: as you stand, lean against the wall, or lounge on the step in the foyer, or when you step forward or backwards on stage as you reply to witty and/or personal questions such as: Have you ever fallen asleep in the theatre? Have you ever left before the end? Have you ever had B.O. in the theatre? Have you ever masturbated in the theatre? Do you think that a step forward is positive and that a step backwards is the opposite?

Prolog (Prologue)

The piece premiered at the Kraków Theatrical Reminiscences festival in October 2011, with the first regular performances held in Warsaw’s Collegium Nobilium Theatre 28 April 2012. Prolog will also be featured at the Trouble 8 festival in Brussels from 30 May to 1 June 2012.

The purpose of the game remains unclear, as does its ultimate winner and loser. The questions asked certainly do provoke us to consider the role of the audience in the theatre, but as it soon turns out, they also serve to sketch a map of differences and similarities between the participants of the game. When you lie on the great white tuffets, your reflection appears overhead along with everyone else’s. You contemplate drawing the web of connections that form between the audience members over the course of the game. All of this appears to induce the participant to perceive the whole event as an encounter with other subjectified viewers, calling into question the traditional role of the audience as subordinate.

Prolog radically broadens the limits of the definition of the theatrical performance, shifting the attention to that which in the theatre has always been obscured by the shadows: the behaviour and, more importantly, the feelings and reflections of the audience. Ziemilski thus dwells on a subject that he has been intrigued with for quite some time: social choreography, not just in the sense of the actions associated with the theatre, but also movements of the imagination. As he writes, “If change comes from within, then what is it that makes us so insistent upon searching for it elsewhere?” The creator of Prolog explores the possibilities offered by social choreography as a tool with which to shift the accents in our perception of reality; to provoke in us a more conscious perception of the web of connections comprising our social identity. The performance is a prologue in that it is the artist’s intention for the audience, their imaginations now stimulated, to leave the theatre with the view of implementing the remainder of the experiment by themselves.

translated by Arthur Barys