MICHAŁ CHACIŃSKI: You are visiting Warsaw for a masterclass at Planete Doc Review festival. But the masterclass is for a limited audience – for film industry professionals who have the ability to come to Warsaw. There are probably many people who can’t participate in the class and would like to hear you talk about the filmmaking process – cinematography, editing or screenplay work. So let’s start with the text, which is usually at the beginning of a film. Do you always work with a script?

WERNER HERZOG: When I work on my documentaries I never have a script. I know what I want to achieve. When you go to Kuwait and everything around you is burning, you don’t need a script. But in fictional movies there is a script of course, though these days it looks different than it used to. When I was starting I had no idea how a screenplay should look. I wrote everything in prose. My script looked like a thick novel. Today, for convenience’s sake, I have a more conventional text because I’ve long been fed up with actors who come and ask where the dialog is. Of course, I try to be flexible because during production life often intervenes in your plans with such force that your eyes are suddenly opened to better solutions that need to be introduced quickly. At another time it turns out that the dialog is great on paper but when the actors read it aloud, it sounds false.

Reportedly on the set of Rescue Dawn the actors discovered you hadn’t looked at the script since writing it a couple of years earlier.

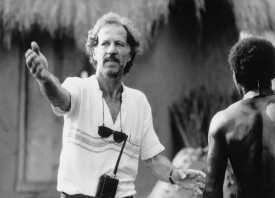

Werner Herzog

Director and screenwriter, author of both feature and documentary films. He was born September 4, 1942 in Munich and grew up in a small village in Bavaria. He studied history, theater and literature but graduated in none because he went on a scholarship to the US where attended film school. He didn’t graduate there either, which didn’t prevent him from making several dozen movies that won awards at major world festivals. Without a doubt one of the most important names in contemporary cinema.

This may sound strange but I don’t really need it. I know what film I want to make. I don’t need to slavishly follow a text that was written in the first place to satisfy the producer and give the actors an idea what the film is about. Rescue Dawn is a feature version of a documentary I worked on 10 years earlier. I knew the story inside out. There was no one on the set who’d know better than myself what would sound false in it. Of course, you need a script, if only for the reasons mentioned above. But you mustn’t allow the script to paralyze you. When you are in the jungle with two actors and a cameraman, sometimes the landscape itself or the light requires you to quickly improvise a scene that will say more about the characters and their situation than a piece of dialogue written behind a desk 5000 kilometres away.

Such an approach probably requires a specific working style. Film sets, especially with stars, aren’t a place where you can do anything fast – there is always the lighting, the soundmen, the set designer, etc.

But the director has to control all this. If the production process inhibits the director's creativity, something’s wrong. That’s why there are situations when I like to escape the whole machine. When I was making Rescue Dawn, which featured a star such as Christian Bale, I’d take Christian, Steve Zahn and my cinematographer, Peter Zeitlinger, jump in a car and go a dozen kilometres into the jungle to find the right place and shoot an important scene. The producers weren’t too happy about this but so what if we managed to find a wonderful hill with a view of the whole area and shoot a scene in the sun which on that day appeared from behind the clouds only for a moment. If we had waited for the make-up people, the production manager, the scenographer and the assistants, nothing would have come out of it.

What about continuity? Aren’t you worried that something may then not fit on the editor’s table? That someone has a backpack in one scene and no backpack in another, that someone’s hair is changed or they’re missing a jacket?

Continuity is one of these magical words used in Hollywood. The camera is ready, the director is on the set, the actors sit at the table and there’s a guy checking for half an hour with a photograph whether a glass of water stands exactly where it stood yesterday. A bad story won’t be helped by a glass standing where it stood and a good story won’t be spoiled by it being somewhere else. My rule in this case is: good naterial always fits together. In fact, it happens during editing that I shuffle the scenes within a sequence and then it turns out that continuity doesn’t matter anyway. When you are too pedantic it kills the spirit of a film. I prefer to work fast because then everyone on the set has energy that shows through on screen. Movies shouldn’t be made as if they were dish recipes but that’s the approach most film schools take.

With such a philosophy, do you accept the presence of the editor on the set?

Normally not but in both my latest feature projects, Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans and My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done, I had very limited time for shooting so the editor was on the set. This allowed us to work faster. We filmed during the day and in the evening we created a sort of prefabricate of the film to see whether we had everything we needed. As a result, in both cases the final version of the film was ready shortly after shooting was complete.

Long-time cooperation helps here of course. In both films the editor was Joe Bini…

… with whom I’ve done a dozen or so projects. That’s why we know how to work quickly and effectively. The way my system works is I watch the footage only once, write a short commentary and I never view all of it again. Out of the five takes of scene 23, for instance, I then have to deal only with the take no. 3 where I put two exclamation marks. Joe sometimes says that I should go back to a different take but I usually say: “Let’s go to the next scene.” I believe in my first impression. But I don’t follow it slavishly either. It happened recently that Joe pushed me very hard on a scene that I didn’t want to include in the film. In Bad Lieutenant, there’s a scene in a car where Nicolas Cage waves his gun and talks to the passengers. Having delivered his lines, he suddenly started to improvise and bare his teeth manically. I thought he’d gone too far and cut the scene right before the improvised part. But Joe, without telling me, included the rest too and told me to watch not the single scene but the whole final half-hour of the movie. And he was right. The whole thing suddenly worked better.

This is possible with a feature film where there is a script and a predictable plot. But how is it with a documentary? Do you shoot a lot of footage that ends up being thrown away?

I never shoot a lot. If you take Grizzly Man for example, about half of the footage in the film was mine (the rest was shot by the film’s protagonist, Timothy Treadwell). We shot two, perhaps three times as much footage as can be seen in the film. And in most cases because I didn’t like how someone had told their story. Quite often I tell the people in front of the camera: “That’s too long. Say it again but in fewer words.”

In fact, Grizzly Man is a good example of the pace I work at. When I got the entire footage shot by Treadwell, it turned out to be around 100 hours long. Watching it closely would have taken 10 days. We had no time for that. After we finished shooting, the producer came to me and said he was very sorry, but he’d like to show the film at Sundance. I said the festival was a couple of months away, so what’s the problem? And he said: well, the deadline for submissions is nine days from now. So we did the imposible, several people helped me select the scenes shot by Treadwell, at the same time I was editing the film and writing the voiceover narration for it, which in the end I read myself. We met the deadline. But working like that you must trust your instincts. Let me say it again: trust your first impressions. A director should avoid intellectualising too much and analysing every second of the material. Leave it to the critics.

With such an emphasis on working fast, have you switched to digital cameras and digital editing?

I still use celluloid and I don’t want to switch to digital yet precisely because celluloid forces you to be economic and precise. If there’s no infinite amount of film on the set – and there never is – you turn the camera on only when there’s something really exceptional to film. It’s a disease of the digital era – people keep shooting, and shooting, and shooting. The camera never stops. I have a student at my film school who recently came with 200 hours of footage and he still wasn’t sure whether he would use anything. He showed us a fast, music video-like synopsis of the 200 hours and at one point I shouted: “Wait, there was a great landscape there!” And he goes, “I have five minutes of it.” I could only tell him that a five-minute static shot of the landscape would have impressed us more than the accelerated version of the 200 minutes of footage flashing on screen. A filmmaker has to trust what they’ve shot and has to know when to shoot. Another example from my school is a puzzle collector filmed by one of my students – a man who has a collection of thousands of puzzle sets from all over the world. My student showed us a film where there’s a fragment showing the man working on a huge puzzle. But then he confessed that he had shot almost four hours of footage for that scene. He filmed from the first piece of the puzzle to the last one and ultimately selected just 20 seconds of footage! That’s stupid. This isn’t how films are made. Directing is an art of selection.

So I do not use digital cameras often, but I do edit digitally. In the creative sense, I see no problem with editing celluloid or onscreen images. The difference is physical. I used to have cabinets full of celluloid on shelves marked with symbols, numbers, text. I knew for instance that on the second to last shelf of the cabinet there was a piece of film with something special. You had to find the strip of film, take it from the shelf and paste it in, and that of course took a lot of time. Digital editing allows me to work at almost the speed of thought. You don’t even have to move away from the table. Of course, the danger of overdoing it exists here too, because handling of digital material is so easy. You can easily make twenty or thirty versions of a scene and get lost in the sea of possibilities. I create one version and if it works, I go on. The filmmaker’s decision has to be firm and final. You have to approach the material ruthlessly.

How much freedom do you give the cameraman? Can they shoot something they’ve spotted without asking you?

We always discuss the key shots but I only work with cinematographers who can “read the situation” and react when something goes beyond the agreed choreography. For my cinematographers, I’ve created something I call “negative definitions.” One of the people who embraced them is Peter Zeitlinger, with whom I’ve made the last dozen of my films. Firstly, don’t do aesthetics, style will come by itself. Otherwise you’ll end up with kitsch. Secondly, there is no looking through the viewfinder on my set. The cameraman has to know what he’ll see with the given lens without actually looking through it. Looking at you across the table I know that with a 35 mm lens I’d see your whole head, arms and half of the door there. But if I get closer by half a metre, I’d need a 24 mm to make the same shot. So my cinematographer has to understand without looking through the lens how much his lense sees. Thirdly, I do the clapper myself. It’s a great instrument that separates the actors and myself from the work of the technical crew. When I operate the clapperboard myself, everyone knows that I’m not a director somewhere on the chair in the corner but that I’m in it physically all the way, just like them. This results in the fourth rule: no chair for the director. You can sit at home. Another rule: I don’t allow monitor playback on the set. Everyone has to know what they are doing. The video monitor gives you a false sense of security and often misleads you. Besides, when there’s a monitor on the set, it becomes the centre of attention. No one looks at the actors and the set, everyone‘s looking into the monitor. Sometimes, but seldom and only because of technical difficulties, I allow the camera assistants to check the shot on a very small portable screen. I myself do it very seldom and only in exceptional situations. I’m not interested in cinema polished at the expense of truth.

How do you get your crew to accept the dangerous locations? You’ve said on many occasions that you take calculated risks, but how can you foresee what will happen on the slope of a smoking volcano?

Of course my collaborators have to decide themselves whether they want to participate in the project. I don’t hide the risks from them. I try to explain honestly and precisely where and in what conditions we’ll be filming. The press has often exaggerated in describing my sets. I’ve been portrayed as a reckless man who doesn’t care about people’s lives, and that’s not true. I believe I’m good at assessing the risk and I never try to do something completely insane. As a proof I can say that no one has ever died on my set. Which of course doesn’t mean that it’s all comfortable and there are no risks. Also, before I ask someone to do something dangerous, I first try ti do it myself to prove that it’s possible. It’s never the case that as director I sit in a cosy hotel and keep the crew in horrible conditions. That’s why over the years I’ve built up a group of people that I work with – we trust each other and we know that we’re not taking advantage of each other. Even the person closest to me on the set – the cinematographer – can decide against shooting a scene if they don’t want to.

Has this happened? Werner Herzog, photo: Planete Doc ReviewMany times. In such case I would take the camera and shoot by myself. I’ve shot many more scenes in my films than anyone suspects. Some films I’ve shot entirely myself though the credits list a cinematographer. It’s happened that only after filming I’d call a cinematographer friend of mine and ask him to allow me to use his name in the credits so that I don’t look like a megalomaniac who’s not only come up with the idea of, produced and directed the whole thing but actually filmed it, too.

Werner Herzog, photo: Planete Doc ReviewMany times. In such case I would take the camera and shoot by myself. I’ve shot many more scenes in my films than anyone suspects. Some films I’ve shot entirely myself though the credits list a cinematographer. It’s happened that only after filming I’d call a cinematographer friend of mine and ask him to allow me to use his name in the credits so that I don’t look like a megalomaniac who’s not only come up with the idea of, produced and directed the whole thing but actually filmed it, too.

Can you reveal any specific titles?

I shot Wheel of Time, though in that particular case it was a decision motivated not by safety but by pragmatism. As a duo with the cameraman we’d have been far more noticeable among the Tibetan monks. It would have been clear right away that we were a professional film crew and people would act differently then. My cinematographer decided he shouldn’t go because his presence would harm the film. Danger, in turn, was a factor recently on location in Asia where I was filming My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done when the riots broke out. Many people were killed, there was a lot of police and military around. We’d have been an easy target with the cameraman. I had to shoot by myself. I was filming with Michael Shannon who said that while he understood why we had no cameraman, he couldn’t understand why the producer wasn’t with us. If they put us in jail, the producer should do time with us!

Does it happen that the crew talks you out of a risky scene?

Seldom, but it does happen. When making Little Dieter Needs to Fly we had no permission to shoot in Laos and couldn’t officially cross the border with the crew. We decided with Dieter Dengler that we could cross the river Mekong, walk 35 kilometres through the jungle, find the remains of the wrecked airplane and film what we needed. I would be the cameraman and the soundman. The crew convinced us that it didn’t make sense. It wasn’t even that someone would surely arrest us. They gave us a more intelligent reason: will it make the film worse if we don’t show the wreck? We decided that in fact we didn’t really need the wreck footage that much. So sometimes, with a good argument, even I can change my mind.

I know that your latest project is in 3D which sounds somewhat surprising. I wonder whether any Werner Herzog film needs 3D for anything.

Selected filmography

Features: Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970), The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974), Stroszek (1977), Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), Woyzeck (1979), Fitzcarraldo (1982). Documentaries: Fata Morgana (1971), Land of Silence and Darkness (1971), Bells from the Deep (1993), The White Diamond (2004), Encounters at the End of the World (2007).

The idea wasn't mine. I’m working for the French ministry of culture. I’m shooting in a cave in southern France – magnificent, discovered in 1994, featuring the world’s oldest drawings. The producers suggested we should shoot in 3D because this would give us better chance for cinema distribution. At first I rejected the idea because we were to be filming two-dimensional, flat wall paintings. But when we went there, I realised the producers were right. The images from 32,000 years ago wonderfully use the walls. The bulges for instance are animals’ humps. Some animals walk out from the niches. With proper lighting you get the impression these images are not two- but three-dimensional. This effect would be lost if you used a conventional camera. Only 3D shows it in full. But please, don’t assume that from now I’ll be doing everything in 3D. This project is special. 3D is very trendy today and the industry has fallen in love with it but I think it’s temporary. 3D works great in those superproductions like Avatar but makes little sense in documentaries, dramas or even romantic comedies. I think when the novelty of it passes, we’ll arrive at the right conclusion that 3D is simply another tool at your disposal, one that should be used for the right project. 2D and 3D cinema will coexist. After all, great works aren’t a result of great tools but the fact that these tools are used by great artists. Kurosawa’s Rashomon still doesn’t need 3D. It’s a black-and-white movie, in mono, and yet it remains one of the greatest films ever made.

translated by Marcin Wawrzyńczak